When it comes to descriptive writing, there will always be the question: How much is too much?

At one end of the scale, we have authors like sci-fi luminary Frederik Pohl, who once famously turned down an invitation to participate in a competition to write a short story of 500 words or less because, “It takes me 500 words to answer the phone.”

On the other end, we have all-round luminary Stephen King, who summed up his approach in his opus about his craft, On Writing, as: “Omit needless words.”

And great authors through the ages have scattered themselves across that scale, from Robert Jordan riffing endlessly about the weather in his high-fantasy tales, to Ernest Hemingway’s fabled six-word story: “For sale, baby shoes, never worn.”

I’m sure there is lively academic debate about which approach is the correct one, but my opinion is the one I apply to most things in life — the sauce needs to match the dish. You don’t eat ketchup on a steak and you don’t put sauce bordelaise on instant ramen.

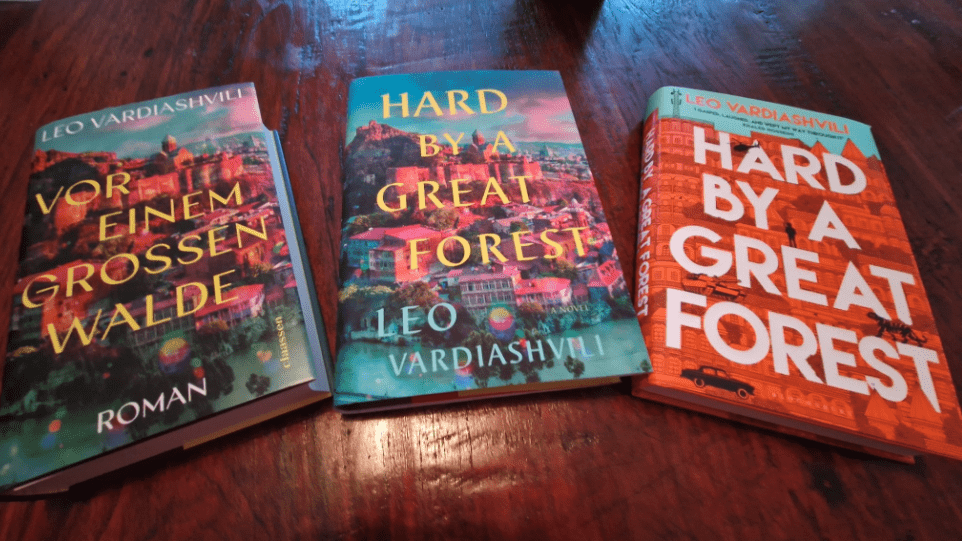

I mention all of this because Leo Vardiashvili’s astonishingly good debut novel Hard By a Great Forest is crammed to the gills with descriptive language.

Similes flow as cool and clear as glacial runoff; metaphors rise and set over it, warming it with their light; and personifications run amok on sturdy legs.

But all this florid language absolutely, positively serves its purpose in this truly wonderful story.

The phrase “hard by a great forest” is the opening line of the story Hansel and Gretel by the Brothers Grimm.

Vardiashvili’s story principally deals with the same thing. Two children set off into a forest in search of something not altogether benevolent. Only, in the original, the trail of breadcrumbs was laid so the children could find their way back out. In our story, the trail of breadcrumbs is how the children are tracking their ultimate goal.

The story is told solely from the perspective of our protagonist Saba, a man who, as a boy, fled post-Soviet Georgia with his father Irakli and his older brother Sandro, and landed in a dingy flat in Tottenham, London.

Irakli is haunted by the spectre of Eka, his ex-wife and the mother of his children, who stayed behind during the worst of the Georgian civil war so that her ex-husband and her children could escape.

Despite having divorced her before war broke out, Irakli is determined to get Eka out of Georgia and give his sons a mother in their new country.

However, time passes and, to paraphrase Vardiashvili’s words: “What once was a promise became a lie.”

What little money Irakli can scrape together is stolen by a con artist and no more is to be found in the wake of steering the boys into their new life in England.

Even though the family eventually receives word of Eka’s death, her ghost ever hangs over Irakli’s head.

Again, quoting from the book: “Grief without closure has a way of fucking with you.”

Once his boys are adults and have their own lives, Irakli gathers the courage to return to his homeland and lay his ex-wife’s spirit to rest.

However, he disappears two months later, after sending his sons a cryptic email.

Sandro, the logical, responsible big brother, sets off in pursuit, but also eventually vanishes after his own cryptic email. And so it falls to Saba to return to his home, which is no longer a home, to find out what has happened to his family.

The above set-up all happens in less than 20 pages.

And then we’re off: Vardiashvili begins spinning us a spectacular story at a steady pace. At its core, it does re-use the sentiment of “two children set off into a forest”.

Usually, but not always, the two children are Saba and Nodar, the man who starts off as a taxi driver and eventually becomes a companion in a journey with increasingly high stakes.

Whenever there are more or fewer than two children on the path, the story finds a way to rectify the number, even resorting to the paranormal to do so.

It is on the opposite scale from King, not only in the “needless words” category — needless but wonderful words, I would like to emphatically state — but in how it steers us in new directions.

Whereas King tends to set you off on a specific path, then grab the steering wheel and send you lurching into a screaming 90-degree left turn into goodness knows where, Vardiashvili is more subtle.

Three degrees here, a couple more there and then, all of a sudden, you’re knee-deep in that sensation that you get when trying to find your lodgings late at night in a strange place. “I could have sworn it was over there …”

The story is also extraordinarily propulsive, almost begging you to keep reading, but in a very subtle way.

It’s less like a parent grabbing you by the hand and yanking you through a public place and more like the same parent placing a hand on your back and nudging you until you’re walking faster than you thought you knew how.

To say it ripples with emotion is an understatement. There is humour and charm by the bucketload and the characters are sympathetic and deeply human, even the antagonists.

And when the incident which incited Saba’s family’s flight is recounted, I actually had to stop reading for a good 10 minutes to regain my composure, such was the underpinning tragedy.

On top of all of this float Vardiashvili’s words. For a man who only started speaking English at 12, his command of the language is astonishing. And he deploys it to great effect, painting a picture of a man torn between two worlds trying desperately to inter his dead to find salvation in, and for, the living.

In summary, let’s omit needless words: I cannot recommend this book highly enough.

Hard by a Great Forest is published by Bloomsbury.

1 week ago

69

1 week ago

69