(This is the third in a series of articles on the Thornhill sabotage and its after-effects. Read Part One and Part Two – Ed)

In late 1982 – two months after the Thornhill debacle – a senior Zimbabwean minister told a journalist that the government had it all in hand: “We are very satisfied that we are in control of the situation… In the past, we would discover who blew up [infrastructure]… after the culprits had left the country.” Yet, now things were different, he suggested. Those involved in Thornhill had been caught, as had many other dissident elements.

“We are very satisfied with the effectiveness of the security forces,” he said.

But he was wrong. The Thornhill investigation was, in reality, a counterespionage train smash. On top of the physical damage caused by South African explosives, much of the air force’s human resources were dismembered by the arrest and torture of innocent officers – and the one guilty party the authorities had in custody, the Thornhill mole, Neville Weir, was mistakenly deemed a minor player.

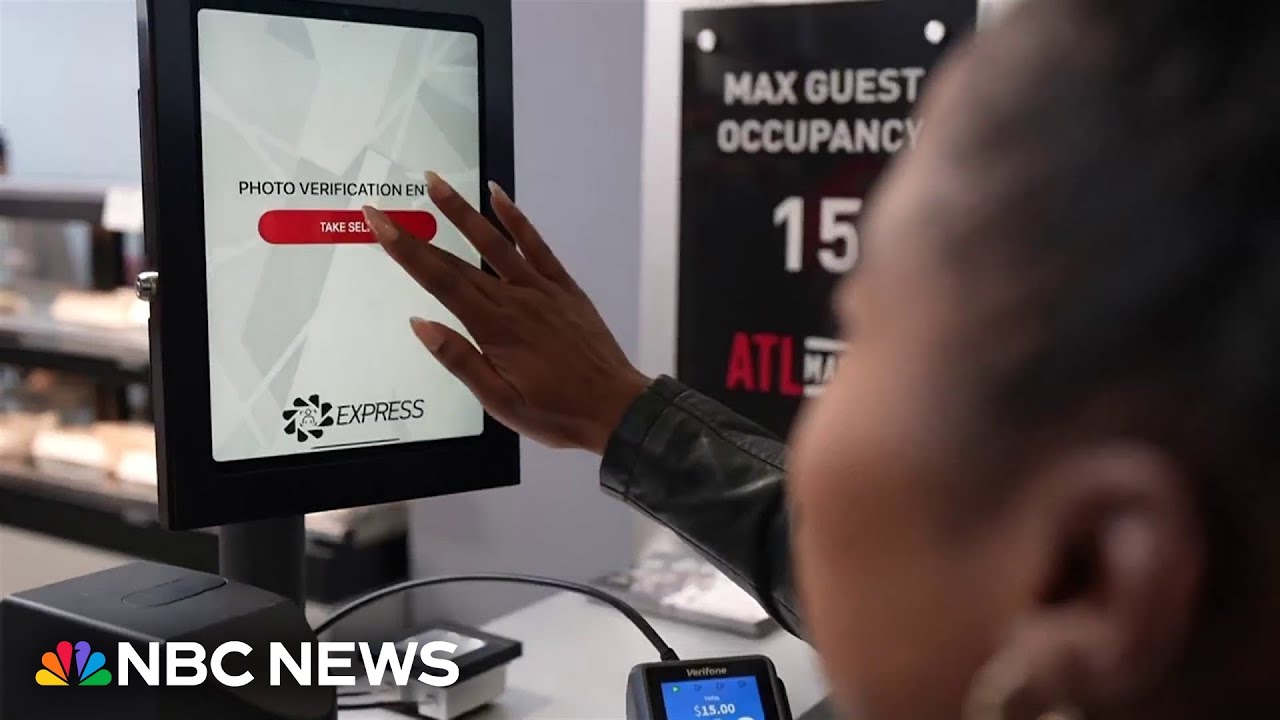

Accused of sabotaging the Thornhill Air Base (left to right): Air Lieutenant Barry Lloyd, Wing Commander John Cox, Air Lieutenant Neville Weir, Air Commodore Phil Pile, Wing Commander Peter Briscoe and Air Vice-Marshal Hugh Slatter. (Photo: Wikimedia)

Another subversive – Weir’s handler, the parliamentarian Donald Goddard – stood in front of the regime’s ministers on a daily basis during sessions of the House of Assembly, often asking questions about the detained airmen, and they were oblivious to his double life.

And then there were Goddard’s compadres on Team Romeo, the South African-sponsored black ops unit that had carried out the Thornhill raid.

These “culprits” had not been identified, and nor had they left the country. They were apprehended years later – or at least some of them were – after committing a string of seditious acts and leaving carnage in their wake.

The ties that bound Team Romeo were fashioned by geography, kinship and war. Its members came from the Shangani, a farming area northeast of Bulawayo, and most were related to each other. All were young men who had fought in elite units of the Rhodesian army during the civil war of the 1970s. Psychologically undemobilised, they were unable to adapt to ordinary civilian life or to accept the new political order led by their former enemies.

Gray Branfield, the group’s recruiter and controlling hand, working from a base near Pretoria for the South African Defence Force (SADF), fitted the same profile. Indeed, that was no accident: faced with the sensitive task of enlisting an operations team in the early days of Zimbabwean independence, he seems to have gravitated to those he knew best and trusted most – people from the area of his matrilineal family, the Ashburners of Shangani.

A private interview with Branfield, which has only recently come to light, reveals that there were four members of Team Romeo. Its leader, Christopher ‘Kit’ Bawden, formerly of a Rhodesian special forces unit, the Selous Scouts, was joined by his cousin, Barry Bawden, an ex-member of the Rhodesian Light Infantry. Goddard, also of the Shangani, had been a Selous Scout, and the fourth operative, Mike Smith, was ex-SAS.

These men, minus Goddard, gained notoriety in the late 1980s when they were arrested, tried and sentenced to death or long prison terms. Factual fragments about their activities, and various misinterpretations, entered the public domain during that process. But the origins of the group, its responsibility for the Thornhill sabotage, and accurate information on its structure and function have been hidden until now.

Put otherwise, the arc from Team Romeo’s genesis through to its active years and fall has remained opaque.

And that wider view is, perhaps, where the most significant thread is to be found. If clan and soil were some of the strands that held Romeo together, then impunity was, undoubtedly, another. The seeds of the group’s untrammelled violence took root years before the advent of Zimbabwean independence and the formation of a hit squad in the country.

Zipra Shangani country club attack

In 1977, at the height of the war, guerillas of the nationalist army, Zipra, attacked the Shangani country club, killing one and injuring four. The Bawdens happened to be there at the time, as Branfield recounted in his confidential interview:

“[Kit’s brother, Guy,] was at the Shangani Club when it was attacked by Zipra. So was Kit and a whole lot of other guys. On the way back from there in the early hours of the morning along the Insiza-Fort Rixon Road to his old man’s farm, he bloody shot a wog [black person] walking along the side of the road.”

The murder of an innocent civilian was soon followed by a coverup, initiated by Branfield himself.

“I was i/c [in charge] of [the police] Sabotage Section in B[ulawa]yo. My guy, Rick Wentzel, investigated it. He said: ‘Look, this is murder, but it is one of the Bawden boys.’ My family, the Ashburners, grew up in that area. I knew everybody there. The Goddards, the Ashburners, we were all interrelated…

“He said he was damn sure it was a Bawden boy involved in it. I took over the investigation, found out who it was and squashed it. We handled it. There were a lot of emotions involved and all that. I got hold of Guy’s old man. We roasted the bugger… his 16-year-old youngster was pulling blacks with a .357 by the side of the road.”

The lack of cultural and institutional checks that enabled Branfield to pervert the course of justice – and what is perhaps the most intoxicating of all human addictions, the power over life and death – led him to seek a similar environment at the end of the war. Not for him, the mundane boundaries to which mere mortals were subject, those of a normal life and the rule of law.

As head of urban operations at Project Barnacle, a dirty tricks department of the SADF’s Special Forces, Branfield could continue operating at the outer edges, with enormous scope to decide others’ fates, controlled only, and in part, by military superiors of the same ilk.

He was joined at Barnacle by other control-averse ex-Rhodesian servicemen, and by his carefully selected posse of fellow addicts in Team Romeo. Bloodshed being both child and handmaiden of impunity, it is unsurprising that killings accompanied Barnacle and Romeo on every step of the journey, before and after Thornhill.

A year before the sabotage, in one of Barnacle’s first operations, Branfield and two of his black operators assassinated the ANC’s representative in Zimbabwe, Joe Gqabi, shooting him 19 times at close range. The South Africans had warned Prime Minister Robert Mugabe’s government that they would take action if ANC military bases were established in Zimbabwe, yet there is no evidence that Gqabi engaged in anything but diplomatic activities in the short period after his arrival in the country.

As for Thornhill itself, the raid may not have been targeted at military personnel per se, but its planning and execution were conspicuous in their disregard for human life. The incendiary devices planted in the aeroplanes were timed to detonate in sequence over a period of around 30 minutes, by which time the base’s firefighters would be expected to have attempted an intervention.

A Zimbabwe air force British Aerospace Hawk jet at Thornhill airbase, Gweru, destroyed on 25 July 1982 #Rhodesia. (Photo: X)

Moreover, various secondary explosions, resulting from the detonation of the jets’ munitions, could be anticipated – and were designed to multiply the devastation – as was the depositing of bombs in a crate of fuel tanks and a heavy machine gun magazine.

In the event, the fact that there was no loss of life was miraculous. Many personnel rushed to the area in an attempt to save the aircraft as bombs were exploding, fires burning, and ammunition and shrapnel flying. In one near miss of many, an explosive blew up inside a Hawk jet as men were trying to push it out of a burning hangar.

The culture at Project Barnacle was such that not even the targeting of former colleagues was a bridge too far. That – and Branfield’s predilection for personal involvement in ‘wet’ actions – appears to have resulted in one of the murkiest episodes in the ex-Rhodesian community’s post-independence history.

Superintendent Eric Roberts was a member of the Zimbabwe Republic Police in Bulawayo and a former member of the Rhodesian police, as Branfield had been.

In November 1982, Roberts had played a part in the arrest of Laurie Wasserman, a former member of the Rhodesian Special Branch who had taken a job with the South African police in Messina. It was to be a fatal intervention.

The Zimbabwean government had given Wasserman permission to liaise regularly with border officials and police in Beitbridge, but the terms of that arrangement prohibited him from going beyond a 15-kilometre radius of the town. Roberts received a report that Wasserman had breached the agreement – that he had been seen in Bulawayo – after which he was detained in Beitbridge, transported to Bulawayo, and subjected to an interrogation before being released.

It was an affair that apparently irked the South Africans – all the more so given that Wasserman was moonlighting as a part-time SADF subversive in Zimbabwe. His arrest had therefore brought with it the prospect that he might break under duress and compromise some of the operations he had been involved in – one of which, notably, was Thornhill. According to Branfield, it was Wasserman who had moved the explosives used for the sabotage across the border; he had driven them from Messina to Bulawayo and handed them to Kit Bawden.

Shot dead

A month after the Wasserman incident, Roberts was shot dead in the driveway of his home by assailants who had hidden in a hedge. That modus operandi was almost identical to the one used in Gqabi’s killing.

Branfield was elliptical about the affair when he mentioned it in passing during his interview. Describing how he had fallen out with the South Africans in the mid-1980s and gone to live in Namibia, he said that “anonymous letters started appearing in the press there about Mr X being involved in this and that. I was accused of killing Eric Roberts and I was accused of doing all sorts of bloody things”. In isolation, that could be construed as a denial – except that he continued: “But some of them only Special Forces knew that, some of the detail. So I assumed it was them trying to pressurise me, get me booted out of Namibia.”

There were, then, “bloody things” that Branfield didn’t do, but the up-close-and-personal assassination of an erstwhile coworker seems to have been among the many that he did do.

The physical evidence also hinted at his involvement. A .32-calibre weapon had been used, as had been the case for Gqabi – although, in a typically heavy-handed and ineffective intervention, the Zimbabweans spent less time investigating a potential connection between the two events than harassing those who might have provided useful leads.

A neighbour, Gary Jarvis, who, with his wife, discovered the body, believed that he may have seen the murderers lurking near Roberts’ house on the night he was killed, and subsequently made a statement to police. He was later arrested after it was noted that he owned a licensed .32-calibre pistol – and belatedly cleared when ballistics tests showed that a different gun had been used.

A gradual sidelining of ex-Rhodesians at Project Barnacle’s base in South Africa meant that Afrikaners began to predominate as the decade wore on. But that did not mean the powers that be were having second thoughts about the subculture. If anything, the latitude that had been given to the Rhodesians motivated ambitious Afrikaners to push them out the door.

According to Branfield, Joe Verster, an army officer appointed as liaison between Barnacle and Special Forces headquarters, “was desperately trying to get into Barnacle. To take it over or form his own clandestine unit”. His intrigues were “being resisted”, initially, by the commander of Special Forces, Kat Liebenberg, but Verster was eventually to have his way after Liebenberg – and Branfield – moved on.

Gabarone raid

Branfield’s “last scene” at Project Barnacle was Operation Plecksy, a raid on ANC safe houses in Gaborone in June 1985. By that time, the targeting parameters had become so wide that even Branfield was becoming critical of them.

Surveillance and planning for Plecksy had taken nearly five years, but when the moment came to implement it, Branfield told his commanders that for “[a]t least three or four of the targets selected… there were no longer ANC guys at the targets”. However, the response was “f..k it, we’re going to hit them anyway…

“When they were warned targets were empty, they refused to change plan. The guys are trained for it so we will go ahead. And they did.”

In Branfield’s view, “They were starting to get arrogant. They were interested in hits. Koppe – they were interested in heads rather than actual real McCoy guys. If the guy is a gook [guerilla] I don’t care who he is. He is legitimate. But they were starting to talk about when any guy expressed an anti-SA sentiment – suddenly, ‘We’ll go and kill the c..t’.”

Branfield’s observations square with the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and other accounts, which noted that among the 12 who died in Gaborone were an artist, a conscientious objector who had just graduated with a degree in mathematics, a school teacher who died alongside his six-year-old nephew, and a 70-year-old refugee.

The growing fixation on ‘koppe’ also included a blatantly racial element. Ahmed Geer, a Somali computer programmer, was gunned down during Operation Plecksy at the same time as his pregnant Dutch wife, Roeli, was attacked while hiding in a cupboard. She was seriously injured by automatic gunfire but survived. Branfield remarked that “Geer was screwing an ANC white girl… She was an ANC activist… They were very chuffed to have shot this white bird while being screwed by some bloody hout. Bloody Dutchmen, I tell you.”

Poor discipline

Branfield’s objections to such profligate targeting were exceeded by his disdain for the ill-discipline displayed by his superiors.

“What actually annoyed me was that our guys were exposed all the time,” he recalled. “I found these guys at the JOC [Joint Operations Command] had been on the piss all the time. The hierarchy sitting in the JOC. When I spoke to them, the hit was taking place that night, but these guys were braaing and pissing it up. They were celebrating before it happened. Inappropriately, they had no thought for the operators.”

And therein lay the seed of Romeo’s demise in Zimbabwe. For if murder accompanied impunity, so too did laxity. That, perhaps, was almost inevitable; the autonomy that attracted individuals indisposed to normal rules would also, in time, breed behaviours that exposed operators to their enemies.

After Branfield left Barnacle, he heard regular reports that the operational silos and other precautions he had assiduously constructed to preserve security were being increasingly disregarded.

He had, for instance, always refused to allow Guy Bawden, the teenage Shangani killer, to join Romeo, but that changed: “Kit used to come down [to South Africa] on occasions and saw his brother… He used to say: ‘Look, Guy wants to go back to Zim. Can’t you make a plan and let him join my team?’ I said: ‘Over my dead body. Once a bloody mullion [madman], always a bloody mullion… He [Guy] was a bit penga [crazy]. I refused… But the moment I left [they] employed him and he became an official Special Forces source.” There was also “wheeling and dealing” by operators – black marketeering with a corrupt Bulawayo businessman, Rory Maguire, who, as Branfield warned his successor, “seems to know exactly what they are doing”.

Then there was the mixing of operations and intelligence teams that had previously been kept separate. People from Romeo, the operations cell, were introduced to those from Juliet, which covered intelligence in Mashonaland, and they were conducting missions together.

Brickhill car bombing

One of those was the car bombing in late 1987 of Jeremy Brickhill, a well-known ANC sympathiser, and his South African wife, Joan. The former was severely injured; his spouse and 16 others in what was a crowded shopping centre car park were also wounded.

Kit and Guy Bawden, along with Phillip Conjwayo, a member of Juliet, were the main players in the operation.

Branfield commented, “Before I left [Conjwayo] was being run … separately. Suddenly he was – everybody was meeting everybody else. Guys were being sent up there. Phillip was based in Harare… Suddenly Kit was introduced to him and then they sorted out Brickhill. They started working together.”

Within a few months, both Romeo and Juliet were to unravel as a consequence of their cavalier cooperation. In early 1988, Romeo (the Bawdens and Mike Smith) and Conjwayo – along with Kevin Woods, an intelligence recruit of Branfield’s from the early 1980s who had been kept out of Romeo’s operations until then – bombed an ANC safe house in Bulawayo, killing an unsuspecting black civilian who had been hired to drive the vehicle carrying the explosives.

Conjwayo was caught because the car was traced to him. Maguire was nabbed after Conjwayo, under orders from his interrogators, phoned his handler in South Africa and asked for cash to be deposited at a dead drop. And Woods was arrested after putting the money in a toilet cistern at Maguire’s service station rather than in a remote location. Kit Bawden managed to flee across the border.

Thus, five-and-a-half years after Thornhill, the spy ring that perpetrated it was arraigned for different crimes. Yet it is a story that had begun earlier – in the Shangani, in mid-1977 – and continued after Romeo was dismantled.

In South Africa, Barnacle morphed into the Civil Cooperation Bureau, or CCB, which, under the jealous and hard-driving Joe Verster, with a smattering of original ex-Rhodesians, oversaw some of the most notorious killings of the apartheid era.

In Zimbabwe, Romeo’s freedom to kill was analogous to much larger and more destructive cultures of impunity that had arisen or grown during the war. The conflict between white and black – and the deadly rivalry between the nationalist movements – elevated those who were willing to do things that ordinary human beings would have baulked at. Like Branfield and his colleagues, these were people not merely accustomed to, but hooked on, the extrajudicial power over life and death, and convinced of its utility.

In that sense, Romeo’s tale is the story of Zimbabwe.

The glaring difference is that the group that came out on top after 1980 has not yet met its end. It continues to rule, to kill, and to foster those who wish to live a life without boundaries. DM

Dr Stuart Doran is a historian and the executive director of the Institute for Continuing History (www.continuinghistory.org), a research centre that investigates major episodes of state-sponsored violence. He is the author of a book on the early years of Zimbabwe’s independence – Kingdom, Power, Glory: Mugabe, Zanu and the quest for supremacy, 1960-87. It was shortlisted for the Alan Paton Award for Non-Fiction.

![]()

1 month ago

94

1 month ago

94